Philippine lullabies or cradle songs are interpreted through music videos, made available in streaming platforms and included in a book in the Cultural Center of the Philippines’ important project, Himig Himbing: Mga Heleng Atin (Sounds for Sleeping: Our Own Lullabies).

This project of the CCP Arts Education, through the Audience Development Division, and relying on the works of ethnomusicologist Sol Trinidad, aims to collect the traditional lullabies in different languages from the country’s different ethnolinguistic groups to popularize and foster wider appreciation for them especially among people today, thus safeguarding these songs that have helped nurture many Filipinos.

Chris Millado, then CCP vice president and artistic director, suggested making music videos out of the lullabies. They tapped young filmmakers, those who joined CCP’s Cinemalaya Philippine Independent Film Festival, to interpret select lullabies. They also engaged contemporary singers to sing the songs with Krina Cayabyab serving as arranger and musical director.

Himig Himbing: Mga Heleng Atin was launched on 13 November 2022 with eight lullabies — the Tagalog “Sa Ugoy ng Duyan” by National Artist for music Lucio San Pedro and National Artist for Literature Levi Celerio; “Katurog na, Nonoy” from the Bicolano; “Wiyawi” from the Kalinga; “Aba-aba” from the Subanen; “Hele” from the Tagalog; “Dungdungwen Kanto” from the Ilocano; “Tingkatulog” from the Boholano Cebuano; and “Ili, Ili, Tulog Anay” from the Hiligaynon — and music videos directed by filmmakers Sigrid Bernardo, Mes de Guzman, Law Fajardo, Teng Mangansakan, Thop Nazareno, Carla Ocampo, Milo Tolentino and Alvin Yapan.

Eight more lullabies were recently unveiled for the second phase of the project with more efforts in dissemination and documentation. “Lubi-Lubi,” “Dandansoy,” “Uyug-Uyug,” “Gonon Klukab Tumabaga,” “O Matas A Banua,” “Tungas kay ta Sampaw,” “Bata Alimahi” and “Ligliway Teng” also have their music videos created by Jerrold Tarog, Zig Dulay, Sheron Dayoc, Doy and Ida Del Mundo, Ma-an Asuncion Dagñalan, Vic Acedillo Jr., Arden Rod Condez and Christopher Gozum, also all part of the Cinemalaya family.

The videos were launched during Himig Himbing: Isang Araw Para sa Mga Batang Sining on 5 November at the Tanghalang Ignacio B. Gimenez or the CCP Black Box Theater in Pasay City. The day-long mini-festival was filled with activities, arts and crafts, designed for children, to celebrate National Children’s Month and to serve as prelude to the CCP Children’s Biennale.

Participated in by different cultural groups, the event included workshops on music, dance and theater; sessions on making puni, T-shirt art, dreamcatcher, mandala, and monoprint on glass; Panaginip Dreamscape, a virtual reality station and installation by artist Joyce Garcia; film screenings; a puppet show; a chalk art and freedom wall station; a sampayan where children could hang their artworks; and a sale of children’s books and other merchandise.

Book and album launches

A major part was the launch of Himig Himbing, for which the theater lobby was decorated aptly with baby hammocks and multi-colored pillows. The book containing the 16 lullabies, Himig Himbing: Mga Heleng Atin, A Collection of Cradle Songs From the Philippines, was launched with a discussion with National Artist for music Ramon Santos; CCP artistic director Dennis Marasigan; and children’s book author Dr. Luis Gatmaitan, and with a performance by indigenous Talaandig Manobo leader and musician Waway Saway.

The book also contains introductions by Santos and National Scientist Maria Lourdes “Honey” Carandang, an article by Trinidad and illustrations by Beth Parrocha.

On the other hand, the album was unveiled at a parking lot beside the theater with singer-songwriter Nica del Rosario performing “Hele” and because to audience’s request, “Rosas,” which was dedicated to former Vice President Leni Robredo and was one of the iconic songs during her 2022 presidential bid.

Produced by CCP and Widescope Entertainment, the album, which features the 16 lullabies with musical arrangements by Cayabyab, can be availed on Spotify and other digital platforms.

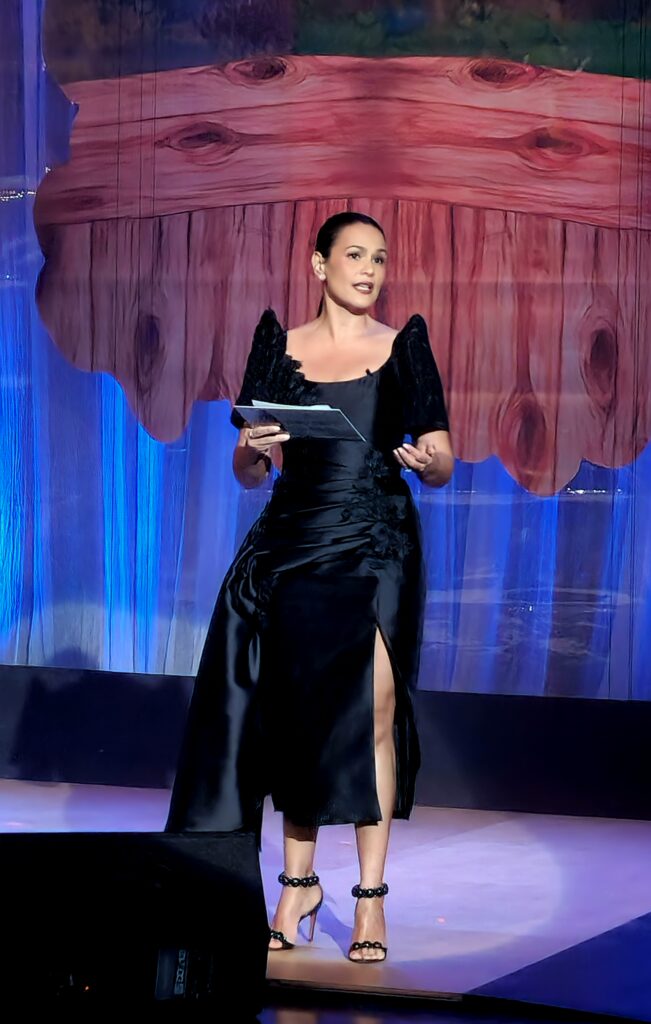

Inside the theater, audience sat on colorful sleeping mats woven by the Sama people with pillows and under umbrellalike decors of kulambo or mosquito nets hanging from the ceiling for the main program, which was hosted by actress Iza Calzado and featuring performances by Bituin Escalante, Baihana, guitarist Ivar Fojas, Aleron Male Choir and Lorelie Macaspac.

With an atmosphere that approximated a bedroom at night brightened by a lamp that cast shapes of light, the videos were introduced and shown publicly for the first time. They are now made available for viewing in the CCP’s YouTube account and Facebook page.

One of the most familiar songs among the collection, “Lubi-Lubi,” whose title may refer to the coconut or the endemic palm-leaf fig, is a very short song that enumerates the months of the year — “Enero, Pebrero, Marso, Abril, Mayo,/Hunyo, Hulyo, Agosto,/Setyembre, Oktubre,/Nobyembre, Disyembre, lubi-lubi.” It is also used as a mnemonic for a child to learn the names and order of the months.

With verses in Bicolano, Waray-Waray and Tagalog languages, its origin cannot be ascertained, but the song was originally recorded in 1970 by Antonio Regalario in Bicol and performed by Restituta Tutañez.

The video is directed by Tarog, known for his 2015 film Heneral Luna.

Another well-known song, the Hiligaynon “Dandansoy” is said to originate in Culasi, Antique. It is often cited among the folk songs of the Philippines. The Mabuhay Singers, Asin and National Artist for film and broadcast arts Nora Aunor recorded their own versions, while National Artist for music Lucresia Kasilag created an arrangement for chorus and piano. Dulay, known for the 2015 film Bambanti and the television series Maria Clara at Ibarra, directed the video version of the love song that speaks to the character Dansoy.

On the other hand, Mindanaoan filmmaker Dayoc, who directed the award-winning Women of the Weeping River (2016), tackled a lullaby from an indigenous group in southern Mindanao, “Uyug-Uyug.”

Sung in old Mansaka language with many words not understood by many Mansaka youths today, “Uyug-Uyug,” whose title means a gently rocking movement, reassures a crying baby that their ailing mother will be healed.

Earliest known field recording of the song is by Marialita Tamanio-Yraola, who recorded it in Davao del Norte in 1972.

“Bata Alimahi” (Foster the Child) from Bohol narrates the many struggles of a mother, which are translated into video by Condez, who is behind the award-winning Cinemalaya film John Denver Trending.

For his music video, Condez said that the persona is “a bird wanting to get out of a cage. She flies all over her cage to find a way to escape. And when she does, it is when she finally feels alive. But unlike a bird escaping, this one has to go back to her cage and get rid of all the things that make it a prison. This bird doesn’t just want to escape; she wants to build a better home.”

Despite the sad situation the song illustrates, “Bata Alimahi” is upbeat.

“I envisioned a dance video to jive with the upbeat melody of the lullaby while still expressing what the lyrics are saying. I have always been a fan of dance as an art form, and I’m happy to direct a dance performance through Himig Himbing,” Condez revealed.

“Tungas kay ta Sampaw” (Over the Hill We Go) is a lullaby in the Kinamigin Manobo language from the island of Camiguin, where the director of the video, Acedillo, hails from. However, like the Cebuano-speaking people currently predominant in the island in northern Mindanao, he is not a Kinamigin speaker and required the help of Nestor Tongol, a Kinamigin expert, to understand the song.

“The heart of it is in the phrase ‘lutaw na bunot’ (floating coconut husk), a local expression which means being useless and with no clear direction. The phrase made the rest of the song make sense. I want to aid the viewers visually in understanding the meaning of the words. We made the lutaw na bunot metaphor more explicit in the character of the music video,” he explained.

Acedillo and his team actually came up with three different storyboards before finalizing the concept “because the words of the song felt philosophical and hard to grasp. The song is a very popular song that was transmitted orally for many generations. Why did it stick for so long, I wondered. Maybe, it is because the song teaches an important lesson in life,” he said.

The Pangasinan lullaby, “Ligliway Teng” (A Parent’s Joy), is emphasizes that a child is a source of joy and relief from stress and sadness, which is a common theme for lullabies. It was published in the book Mga Katutubong Awiting Pangasinan/Cancansion ng Pangasinan by the Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino in 2002.

In creating a video for this, Gozum said, “I showed a young woman who does not value the love of her mother, but in the end arrives at a stark realization that it is in her mother’s unconditional love that she will always fall back into when the world turns against her.”

“The staging of the film is grounded on the documentary realism of our chosen location which is Dagupan City, Pangasinan. The location provided a lot of ethnographic details and the creative process is highly collaborative with the actors and the crew,” he added.

For the video for the Pampangan lullaby, “O Matas A Banua” (Oh Great Sky), director Ma-an Asuncion-Dagñalan wants to show how parents pass their knowledge and inculcate values to their child through growing plants and preparing a dish, a metaphor on how parents prepare their kids to be adults.

“In some societies, a lullaby is used to pass down a cultural knowledge or tradition, and not just a song that is usually sung or played for the children. As the proverb says, ‘You reap what you sow.’ When parents plant good morals and values in their child, their children reap great consequences. A child’s future is shaped by present actions,” said the director of Blue Room, which won Best Film at Cinemalaya in 2022.

She incorporated scenes of farming and cooking, two practices known in her home province, in the music video together with contemporary dance. She also inserted scenes from Pampanga’s history in resisting colonial rule as the song mentions revolutionary heroes such as Jose Rizal and Andres Bonifacio.

“This was very exciting for me because it is my first time doing this process, and I guess, it’s also the first time for CCP’s Himig Himbing. Carlon did a very creative and interesting choreography — which helps the storytelling of the whole music video,” said Asuncion-Dagñalan about the process in making the video.

‘With Himig Himbing, they have become windows through which we can have glimpses of the diversity of Philippine cultures, especially pertaining to childhood and values that are passed on. They have also become sparks for other artists to tell stories, waking our souls up and engaging us to remember and to dream.’

The music video for “Gonon Klukab Tumabaga” is created by esteemed screenwriter Clodualdo del Mundo Jr. and his daughter Ida, who wrote and directed the 2014 film K’na, the Dreamweaver, set in a T’boli community.

This time, she tackled a lullaby from an ethnic group closely associated with the T’boli and also from the same area in southern Mindanao, the Blaan. “Gonon Klukab Tumabaga” (My Childhood Gong) was first recorded by Morito Parcon in 1970 in Marbel (now Koronadal City), South Cotabato.

“It was very interesting to hear the lullaby for the first time. It doesn’t sound like the usual gentle lullaby. I knew it would be a challenge. Krina’s arrangement greatly influenced our interpretation in the flow of movement in the choreography and even in the dark ambience of the visuals. With the trance-like music, we are lulled into a dream state, where past, present, and future dance together,” Ida shared.

Del Mundo collaborated with choreographer Ronelson Yadao, as well as production designer Eric Cruz, director of photography Eric Liongoren, and editor Cindy Custodio to create a music and dance video that tells a story of a father in different realms or generations and his young son who grows up within the dance, using water as image and inspiration for the movements. She also wants to highlight Blaan culture.

“I want to make sure that the Blaan culture is well-represented. At the same time, Ronelson and I discussed a lot about avoiding cultural appropriation in our interpretation of the music. I was able to work with videographers from South Cotabato who had footage of the Blaan prayer ritual in the water that uses the gong, as well as videos of Blaan dancers. We hope to accurately represent the Blaan culture through these video clips, while the contemporary dance is an homage to the indigenous music and culture. The projections are a play on indigenous culture presented using technology,” Del Mundo said.

These lullabies, which are primarily used in lulling a child to sleep, have several functions. Marasigan said that these connect the child to their own culture and community. With Himig Himbing, they have become windows through which we can have glimpses of the diversity of Philippine cultures, especially pertaining to childhood and values that are passed on. They have also become sparks for other artists to tell stories, waking our souls up and engaging us to remember and to dream.