Ian Morley’s new book analyzes in detail urban planning in the Philippines during the American period and post-war years. He posits these developments in the country’s built environment as something truly Filipino.

Titled Remodelling to Prepare for Independence: The Philippine Commonwealth, Decolonisation, Cities and Public Works, c. 1935-46, the book is published by Routledge in Oxford and New York as part of its series on Research in Planning ang Urban Design.

This is Morley’s second book on the Philippines with the first, American Colonisation and the City Beautiful: Filipinos and Planning in the Philippines, 1916-35, published in 2019 by the same institution.

Morley is an Associate Professor at the history department of the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Grounding it on the idea that these developments were done by and for Filipinos, the book, as Morley notes, “explores the Filipino side of decolonisation and the management of the built environment in the years immediately prior to self-rule.”

The plans for urban developments in Manila, Quezon City and other parts of the country are argued as an assertion of identity, pride of place and being independent — that is, capable of advancing plans and programs bereft of colonial influences.

This is with the exception perhaps of the Japanese occupation years when the Japanese introduced their concepts for structures with emphasis on ventilation and the country’s tropical climate, put forward the greening of public spaces, and improved and repaired roads and bridges in Greater Manila.

Quezon City

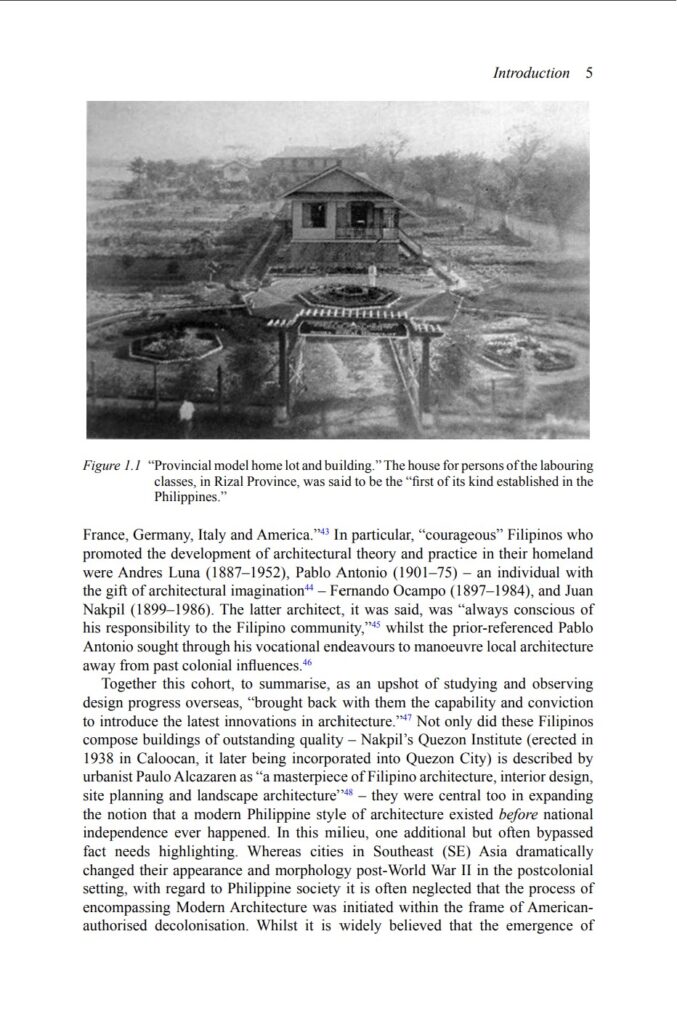

Morley notes that urban planning in the country “was dominated by concepts and principles aligned with civic designing” from 1905 to 1941. With the establishment of the National Housing Commission in 1941, however, the planning shifted to the advancement of livability with emphasis on dignified housing.

The book zeroes in on Manila and Quezon City, giving more emphasis on the development of the latter from plans prepared by Henry Frost with Juan Arellano and Alpheus Williams in 1941, and by Juan Arellano with other architects in 1949.

The 1941 plan is noted for its grid-type morphologies of the planned national capital, but the author weighs heavily on the 1949 plan that, according to him, has the wholistic approach, from the social to economic, political and aesthetic factors.

The urban design of Quezon City is a response to the overcrowding and blight in Manila, giving dignity to the working class through convenient housing plus placing every aspect of the new city’s components in zones, and with the addition of public parks and open spaces.

Here, Morley argues that the urban design of Quezon City is “where nationhood, monumentality, sense of place, progressiveness” are evident of a decolonized urban planning.

Antonio Toledo

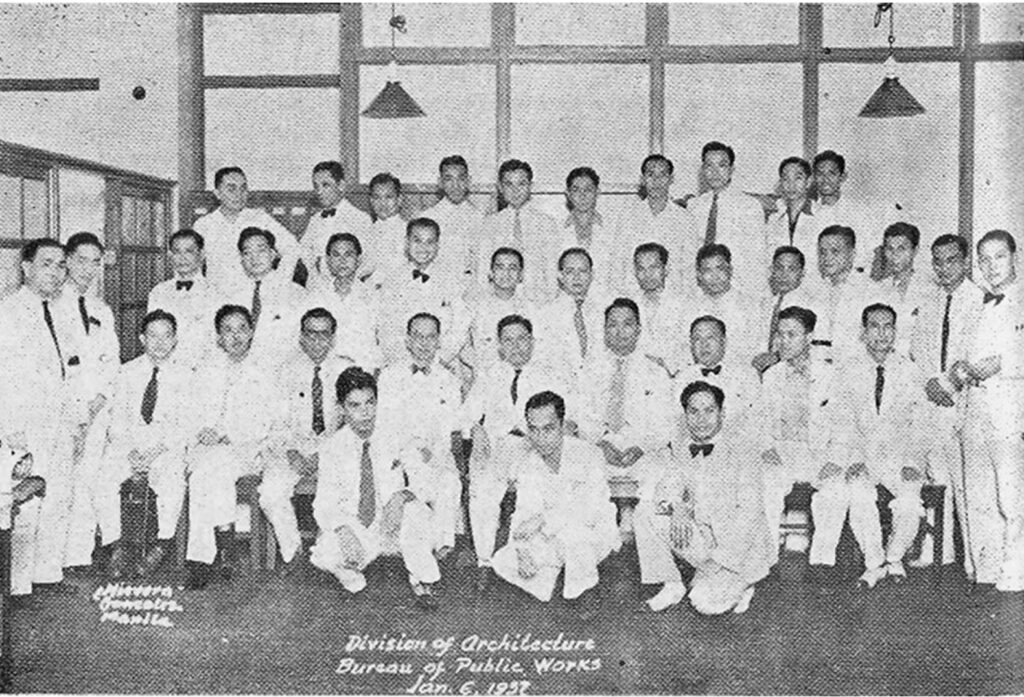

During the American era, one of the country’s leading architects was Juan Arellano, the supervising and later consulting architect of the then Bureau of Public Works.

Arellano’s contemporary was Antonio Toledo, both described by Morley as not “docile puppets of the American colonial regime,” as their ideas and design were approached with a nativist stance.

Morley asserts that, like Arellano, Toledo should be put on the same pedestal as the latter for shaping the urban form in a big way.

Toledo designed roads, parks and prominent buildings in and out of Manila. Among others, he prepared the development plan of Malate Park (later Harrison Park) in Manila, the greening of Dewey (now Roxas) Boulevard, and designed the current Manila City Hall.

Speaking of Manila, Morley highlighted the widely overlooked Ordinance 2830 or “An Ordinance Providing for the Zoning of the City of Manila” enacted in October 1940.

This first-ever zoning ordinance of the city created zones within Manila, which include residential areas, parks, industrial places and military reservations.

What is important in this ordinance is the regulation of heights “in accord with plot widths and, for buildings lining the city’s many plazas, the size of the public space would regulate the heights of new buildings.”

Post-war years

Also discussed in the book is the reconstruction following the destruction caused by the Second World War.

Morley laid out government projects addressing the widespread damage and ruined infrastructure, the construction of roads and overpasses, housing projects in Manila and Quezon City, the rise of modernist buildings and the development of subdivisions outside Manila such as those in neighboring Makati.

The author says the plazas redesigned by Arellano and Toledo in the provinces in the 1930s such as Iloilo and Guimaras were again redesigned in the 1950s, this time by Federico Ilustre.

Overall, Morley’s work is a vital source material to an urban planner, historian, cultural worker and policy maker for the understanding of the planning and development of the country’s urban sprawl during the American colonial period, the Japanese years and the years after World War II.

These include the ideas, concepts and plans of past urban planners in shaping key Philippine cities, which, in a broader sense, shaped the Philippine built environment today.