Raffy Alunan once feared being caught in a furious exchange of hot lead.

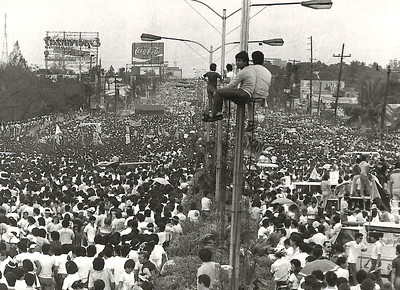

It was 1986, and he was out in the streets partaking in a fast-moving montage of events that restored democracy and ousted a dictator.

Years later at peacetime, a “better tomorrow” he helped win, saw him grappling not with the business end of a gun, but with national amnesia — misleading revisionism, even, that strips the popular revolution of its sacred-cow status.

Silver Linings (2019), which Alunan co-authored, ignites a faculty that now lies mostly dormant in a generation dogged by rumors and anti-yellow sentiments.

Either a country on fire was billed in the day on rosy headlines or martial law was good because it neutered Communist expansion.

A book tour around colleges began in earnest, but young students and armchair historians opposed Alunan’s side of history with some kind of reprisal: “Never believe everything you hear about Edsa!”

He was baffled.

“We said, ‘We were on Edsa. We’re telling you what we experienced on Edsa. You’re telling us not to believe what we experienced?”

It didn’t make a lick of sense where the world has come to; “unbelievable” was how Alunan phrased it.

But one can look the other way to make sense of its meaning: That some of what really happened during Edsa was, indeed, hardly believable, even to the ones who stood there powerless while they witnessed it, and made special by it.

Because miracles happen even at a time where out-and-out lies, excreta and gross misrepresentation of facts was general tenor. And they happened on Edsa.

Alunan belonged to two groups that converged at Plaza Miranda in the thick of the First Quarter Storm in 1969 and 1970.

The fit of nationalistic frenzy peaked after the murder of Ninoy Aquino.

From 1983 to 1986, Alunan barreled through the streets and figured in sporadic uprisings.

On the days leading up to 25 February 1986, defense minister Juan Ponce Enrile and lieutenant-general Fidel Ramos had defected from Marcos.

Manila archbishop Jaime Sin was on the radio, in an impromptu invitation to a peaceful shield mob to buttress Aguinaldo and Crame.

Meanwhile, Alunan was setting up emergency-ambulance services in the off-chance the presidential orders really threatened direct action.

On Edsa-Ortigas intersection, he clambered up Marine trucks in a convoy led by general Temy Tadiar and appealed to the soldiers’ baser capacity for rational thought:

“The stories you’re being told to rescue the people in Crame because of the commies that are surrounding them is a big fat lie. The people in front of you cannot be communists. They’re nuns, mothers, children.”

They were teachers, farmers, laborers, volunteers. It was a man spading his garden. A boy with a cane.

Alunan went up to where Gen. Tadiar was, or at least safely within earshot. The people in the armored car of Tadiar were huddled over the receivers. And guess who issued on the radio?

Temy’s uncle, Fred Tadiar.

Fred was then University of the Philippines College of Law dean. And, and that juncture, Temy’s voice of reason.

“Temy, I am here at UP. Listen to me. Do not follow the orders of Marcos. Those are illegal orders! Believe me when I say they’re illegal. Turn back!”

Temy took it as a hint to retire.

That evening, Alunan went to Santolan where a group of students, priests and Christian educators were attacked the morning after.

He bumped into a group that survived tear gas, among them a man he knew fondly from Bacolod.

Tearing up, the man surrendered to Alunan’s shoulder: “‘You know, I forgot to say goodbye to my wife. I almost died.’”

The dispersal diffused the crowd with smoke, but the winds shifted so that the delousing cloud went back to the direction of the government.

The smoke screen receded and revealed the onward march of a phalanx of marines bristled with fixed bayonets.

“Please. We’re religious. We’re students. We’re unarmed. We’re fellow Filipinos. We’re for peace,” the man implored.

The marines appeared impenetrable — out for blood, even — now poised in its resolve to subdue flower power with brute force.

The man welled up.

“I asked, ‘Why? What happened?’ He said, ‘A soldier lanced me, but very lightly. The group then laid down their rifles and flashed the ‘Laban’ sign,’” Alunan, to this day, couldn’t believe his words. “They defected to Crame!”

During the day, words had also been out about a portent that met two Air Force F5 fighter-jet pilots sent to attack the dugout.

“What they saw flying above Santolan, Boni Serrano, was a crowd morphing into a cross — a cross of humanity. So, the pilots said, ‘No. It’s a sign. We’re not going to do anything.’”

In other news, Alunan recalled, was a battery of howitzers positioned at Ultra to shell Crame.

Instructions were issued, and the soldier manning the artillery pulled the lanyard.

Nothing happened.

The commander protested his order.

The soldier tugged at the trigger but the mortar still failed.

“They thought the barrel was empty,” Alunan shared. “So, they opened the chamber. A shell came out. They put it back in.”

“’Fire!’”

Silence is the rare language of revolt, the sound that met the soldiers in a universe that wanted Marcos no more.

“The commander said: ‘That’s it. Let’s get out,’” recounted Alunan.

“Unbelievable.”