(Part 1)

This is the story of two friends who loved their country. Loyal to each other to the end, they worked together toward serving their people while meeting head-on the challenges of governance, peace imperatives and development in a post-Marcos scenario.

Coming from diverse ends of the archipelago, fate brought them together — one the President of the Philippines, the other his secretary of Interior and Local Government.

Fidel V. Ramos was chief executive of the land from 1992 to 1998. One of the two heroes of EDSA, he had risen through the ranks, an Annapolis graduate, head of the Philippine Constabulary and, in February 1986, chief of staff, a position that had eluded him for years, and one that he would not have reached had the EDSA uprising failed. He eventually became Secretary of National Defense. He successfully crushed nine coup attempts against the Cory Aquino administration.

Rafael “Raffy” Alunan III was a private-sector executive. He grew up in his home province of Negros Occidental, where his family was engaged in sugarcane farming.

The times were difficult in the mid-1980s, as the whole country had been suffering for the longest time, with a hungry child from Negros making it as the international poster boy of poverty and malnutrition. The assassination of Benigno Aquino Jr. precipitated an economic, political and social crisis.

Ramos, a key player in the military, was perceived to be the gentleman officer who was an underdog, bypassed the president of the Philippines, his cousin, when the latter instead chose General Fabian Ver as the Armed Forces of the Philippines chief of staff.

EDSA 1986 is a story that the whole world knows, although its retelling has produced various versions.

Alunan was one participant in the People’s Revolution. At that time, he was one of those who had rushed to EDSA in response to the call of Cardinal Sin for the Filipino people to protect Juan Ponce Enrile and Fidel V. Ramos who had declared their loss of faith in the Marcos government.

This, he shared in a tete-a-tete when he called on the publishers of the DAILY TRIBUNE, Willie and Chingbee Fernandez. As he had a story to tell, the bosses of the daily called us, editors and feature writers, to listen and join them for coffee and pastries.

Alunan did not disappoint. It had been years when we last had sightings of this popular cabinet member. He was handsome then and despite the advance in years, has kept to his good looks. The articulate official, whose many television appearances projected him as a powerhouse of first-hand knowledge and an authority on matters of local governance, peace-building, among other matters and issues of national import, has remained a pleasant and smart speaker who speaks from the heart and his keen memory.

In this private conversation, Alunan was fortright, his narrative riveting, his diction flawless as of a La Sallite to the manor born, and his manners impeccable, if relaxed and friendly. No airs. One could tell this man was and is telling the truth.

Indeed, as his testimony would bear out when two great men with noble intentions unite in action and purpose, good things come to fruition.

In the case of Rafael Alunan serving as a cabinet secretary under President Fidel V. Ramos, the result was of two gentlemen accomplishing heroic acts for their country.

An officer and an activist

Both gentlemen can lay claim to being descendants of public servants. Alunan III is the grandson of his namesake, Rafael Sr. who served as Secretary of Agriculture and Secretary of the Interior during the presidency of Manuel L. Quezon in the Philippine Commonwealth.

FVR’s father, Narcisco Ramos, a prewar legislator and founder of the Liberal Party, became Secretary of Foreign Affairs during the presidential administration of Ferdinand E. Marcos Sr.

Despite the similarity in their family backgrounds, one grew in the South and the other in the North. The Alunans were Ilonggos. The Ramoses were Ilocanos.

Their paths differed in their youth. Eddie Ramos attended the United States Military Academy in West Point, while Raffy Alunan, after graduating from high school at De La Salle Bacolod, enrolled at the De La Salle University Taft, reputedly a rich boys’ school.

And yet, he was not one of the glamour boys, no matter that he was perceived as such because of his good looks and his propensity to smart grooming. Instead, he became an activist during the First Quarter Storm. “I belonged to the first radical class in La Salle,” he revealed. “A classmate of mine was Chito Sta. Romana. We demonstrated in the streets in 1969 and 1970. UP was, of course, the lead. All the other schools followed. And Plaza Miranda was our center of gravity.”

After acquiring his Bachelor’s degree in Political Science and Business Administration, he joined the Filipinas Synthetic Fiber Corporation in 1974. He was only 26 years old. The company chairman was PL Lim, Charlie Palanca its president. Cesar Concio Jr. was the general manager. He became an executive.

Pepe Diokno for a neighbor

In 1983, Ninoy Aquino was assassinated. “The flames of protest was rekindled,” he recalled. “I was a street protester from 1983 to 1986.”

On 22 February 1986, when the revolt started, “we naturally gravitated to it,” he shared. “I belonged to two groups — the Manindigan (Take a Stand), which was composed of businessmen and professionals and was headed by Jimmy Ongpin, its chair, and Ramon del Rosario, who was its president; and the Kaakbay, which was led by former Senator Jose ‘Ka Pepe’ Diokno, a fellow La-Sallite. The Dioknos were my neighbors in New Manila. Our families knew each other.”

Of the coup d’ etat that RAM and Johnny Ponce Enrile were hatching, “Jimmy knew because he had his links to the Reform the Armed Forces (RAM) and his brother Bobby’s circle in the Marcos cabinet, while I had connections to RAM and the Manindigan. And I could read the signs. Trouble was coming. So when it erupted on 22 February, I was moving from one group to the other. Manindigan and also Pepe Diokno.”

Alunan first joined the emergency ambulance service set up by Diokno’s group. “ I proposed to Pepe Diokno for KAAKBAY to hastily form a volunteer ambulance service for the Cardinal Santos Hospital. We linked ourselves to the Cardinal Santos Memorial Hospital in Greenhills West. We positioned ourselves at the EDSA-Ortigas intersection.

“We anticipated casualties in case Marcos went for the jugular. And we would have to bring casualties to the hospitals.”

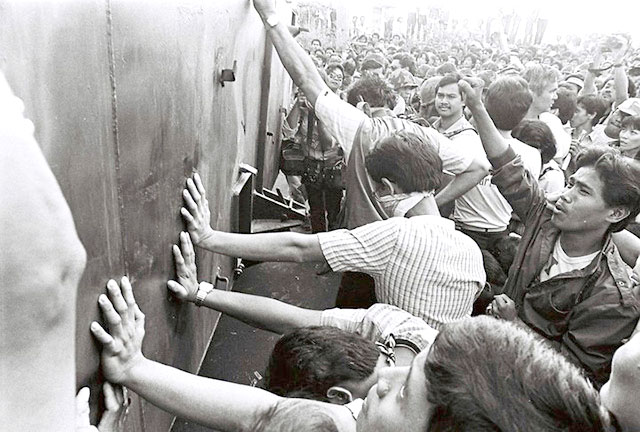

The crucial events that led to the downfall of Marcos thus unfolded. “The marines were blockaded right at the EDSA-Ortigas intersection on day two. My companion from Kaakbay and I would climb up on the sides of the marine trucks to talk to the drivers.

“’The people in front of you are not communists,’ we told them. ‘They’re nuns, they’re mothers, they’re children. They cannot be communists. The story that you’re being told to rescue the people in Crame because the communists are surrounding them is a lie. It’s a big fat lie.’”

The next few hours, he recalled, brought in more people, including prominent personalities. One of them was Ninoy’s brother, Butch Aquino, who was the godson of Raffy’s grandfather, Rafael Alunan Sr. (the first Rafael and Benigno Sr. were friends and both belonged to the Quezon cabinet) went to Santolan at Boni Serrano Avenue.

“The following early morning, a group of Lasallites and Ateneans, Jesuit priests and Saint John La Salle Christian brothers were attacked. When that ordeal was over, it was followed by the defection of General Sotelo of the Air Force.

“After they landed in Camp Crame, the doors of Crame were swung open on the mistaken belief that Marcos had fled. Everyone was cheering already. I remember that was a false alarm. And so we were inside the camp and we were told to leave because the gates had to be closed again.

“So my wife (Elizabeth) and I just mingled with the crowd outside. And that’s where we bumped into people who came from the Boni Serrano area and had experienced the tear gas. The tear gas attack was followed by a phalanx of marines with fixed bayonets.

“We bumped into Rick Pijuan. We knew each other from Bacolod. He cried on my shoulder. And he said, ‘You know, I forgot to say goodbye to my wife. And I almost died.’ He relayed that they had faced the forces of Marcos when they were attacked by tear gas. But the wind shifted and the tear gas went back to the soldiers, the ones who fired.

UP Dean pleads with nephew Temy

“‘And then, this platoon of marines under General (Artemio ‘Temy’) Tadiar, they had bayonets and they marched toward us,’ Rick related. ‘We told them that we belonged to the religious orders. With us were unarmed students and we’re all Filipinos. The Marines didn’t listen. They just went on. Finally, they reached us. And the bayonet hit me.’

“He was hit very lightly but to his surprise, the soldiers stopped attacking. They put their rifles down and they flashed the ‘Laban’ sign. They defected to Crame. Rick was crying when he related the story to me. ‘What happened to me was unbelievable.’ He wept unashamedly.”

News traveled fast. And soon, he was hearing stories “about the Air Force pilots. There were two jets, F-5s that were flying. Their orders were to attack Crame. But since they saw the crowd on EDSA and then, the crowd here in Santolan and Boni Serrano, what they saw was a cross. What they saw was a cross of humanity. So they said, it was a sign. They decided not to bomb the people.

“And here’s another story which was verified later on. I found out that this story was true. There was a battery of howitzers positioned at the Ultra stadium. They were supposed to fire at Crame. The order was given to fire and they pulled the cannon. They pulled the lanyard. Nothing happened. So they ordered again. Fire! Again, they pulled the lanyard. Nothing happened. They thought that there was no bullet. They opened it and the shell came out. So they put it back in. Fire! Wala pa rin. And then the commander said, ‘Okay, that’s it. I’ve had it — no more. Let’s get out. Let’s get out.’ Parang that was another sign. Unbelievable.

“General Temy Tadiar and his men were at the intersection. They could not move farther because they were blocked on EDSA. All along, I was with Ed Garcia, the son of Marcos Health Secretary Paulino Garcia. He was a member of Kaakbay. He and I were going up the marine trucks. We were going to tell them, ‘Hey, you know, these people aren’t communists.’ After a while, there was a standstill. It became very quiet. We went forward to where Tadiar was. He was the leader. He was the leader of the convoy. And I knew the guy who was beside him, the number two guy, Percy Subala. I said hello to Percy.

“Anyway, the people around the armored car of Tadiar turned on the radios. And guess who came on air? His uncle, Fred Tadiar, dean of the College of Law at the University of the Philippines. ‘Temy, this is your Uncle Fred. I’m here in UP. Listen to me, your uncle. Do not follow the orders of Marcos. Those are illegal orders. Believe me when I say they’re illegal. Turn back, turn back, turn back.’ The rest is history. Temy didn’t proceed.”

Special Action Force

The first time Raffy came across the group of President Ramos was when he encountered the Special Action Force, which was guarding Crame. The group had been organized by Fidel V. Ramos who was Philippine Constabulary Chief. By the time, the EDSA Revolution took place, FVR was deputy chief of staff of the Armed Forces of the Philippines, next in command to Fabian Ver.

The SAF went to Crame when they found out that Juan Ponce Enrile and Fidel V. Ramos had holed up there. “They guarded Crame. I was at Annapolis with a group of cousins and friends when I came face to face with them. That evening we were expecting an attack through Annapolis and through Santolan.

“We were armed although we were not organized. But armed, nevertheless. We linked with the SAF team that was at the VV Soliven Building. So, when we saw them, we said, ‘Look, in case something happens, we’re going to open our trunks and we’re going to get our firearms. Consider us your reinforcements. But since we’re not trained for this, you better tell us what to do. Okay. Nagpasalamat sila (They thanked us) that we were there and ready to do our part in defending them. They were very thankful.”

A week or two later, when it was all over, there was an event in Crame. Alunan bumped into Ramos, only two weeks at his post as AFP Chief of Staff. “We said our hellos. My brother knew him. They were friends.”

Later, when Enrile left as Secretary of National Defense, FVR took over from him. Rene de Villa next became chief of staff.

Through it all, Raffy was in the private sector. In 1988, President Corazon Aquino appointed him as Undersecretary of Tourism. He came in very much qualified. He acquired his MBA degree (Senior Executive Program) from the Ateneo de Manila University in 1981.

Peter Garrucho had been appointed as Tourism Secretary. When Tony Gonzalez left, one of his undersecretaries, Wally Reyes, went on leave.

Being neighbors and family friends, Raffy and Peter were in the latter’s home in New Manila when DoT Undersecretary Narz Lim called.

According to Raffy, the telephone conversation went, “Hey, Peter, Tony Gonzalez is leaving. President Cory is looking for a replacement. Do you want to take over? And we’re also looking for an undersecretary. Peter said, ‘Well, Raffy is here.’”

To be continued on 26 February