Italy recently brought an entire opera-house bombast to Tondo.

Over lunch weeks before, Italian ambassador to the Philippines Marco Clemente called it “an experiment.”

“With apes?” I thought.

We’ve seen baby monkeys get attached to surrogate mothers; elephants that paint. And if a concert of intelligent parrots can sing like castrati, perchance an art-inclined lad could rise from the soup lines and dream.

I rephrased my question: “Bless your dear heart, Your Excellency, that’s rich from you, but definitely beyond our means.

Ambassador Clemente could not be conquered. Even with a quick summary of gritty news and Manila’s best gore, he was not going anywhere.

In the ticking windup to his retirement in June, His Excellency has been very sensational with a few Hail Mary strides on culture to leave a better Philippines than when he first found it.

If art were really a mirror to the human condition, the opera in Tondo was going to be it.

At a gallery a few months back, I was transfixed by an abstract rendition of what I thought was a vagina.

“This, here, is one of the grandest masterworks of the great French Crotte de Nez,” the curator bellowed, cupping his long face to impose his view on it. “I think, it’s about the cycle of life and the depravity of man abetting its decay. In all its glorious majesty.”

Others were just as struck with glib as I was, thinking too hard about how else to look at it.

“A woman’s flim-flam, larger-than-life, is how I’m supposed to think it is,” I snapped. “And, if you can pardon my French, we can all let ourselves be brilliant now and rub art with our Johnny Macs.

Everybody is just as endowed with a unique measure of madness. But our thinking society can sometimes become obsessed with pretenses and meaning.

It felt just the same at the Ateneo’s Arete on a recent weekend, in an opera night that twin-billed Giacomo Puccini’s “Suor Angelica” and “Gianni Schicchi.”

It was the predominantly rich type, and maverick ones — a man walked in the hall looking like Jesus with a magic conch shell, and sat on a chair with his name on it.

The curtains parted. The strings began. And, momentarily, we’re trained on a band of nuns screeching penetrating Italian.

That’s opera for beginners: Spend two grand in the orchestra and, in no time at all, you crane your neck and begin to sulk: “Why is it called subtitles when it’s overhead?”

The choreography and musical direction were key thrills and definitely impossible to flag. It’s like following Charlie Chaplin in “A Woman of Paris.”

But, unlike silent films, once you’re lost in a sequence, it would be very difficult to second-guess, let alone relate, and suddenly it was like dull talking and ceremony.

It was partway along an aria that I began to wonder how much farther I could hold out.

Still, I pretended to concentrate with a vain and pensive gaze, stifling my cough between solos and discreetly keeping tabs on Facebook alerts in my pretentious attempt to be polite.

I took my cues from two old women behind me when they laughed, and felt miserably left out when I didn’t get it.

It was an exclusive laugh — boisterous and amusing at the same time — the kind that raised an eyebrow to examine your upbringing in disdain: “I live in Ayala, Alabang. You?”

I wondered how I looked in semi-darkness guffawing like a baboon.

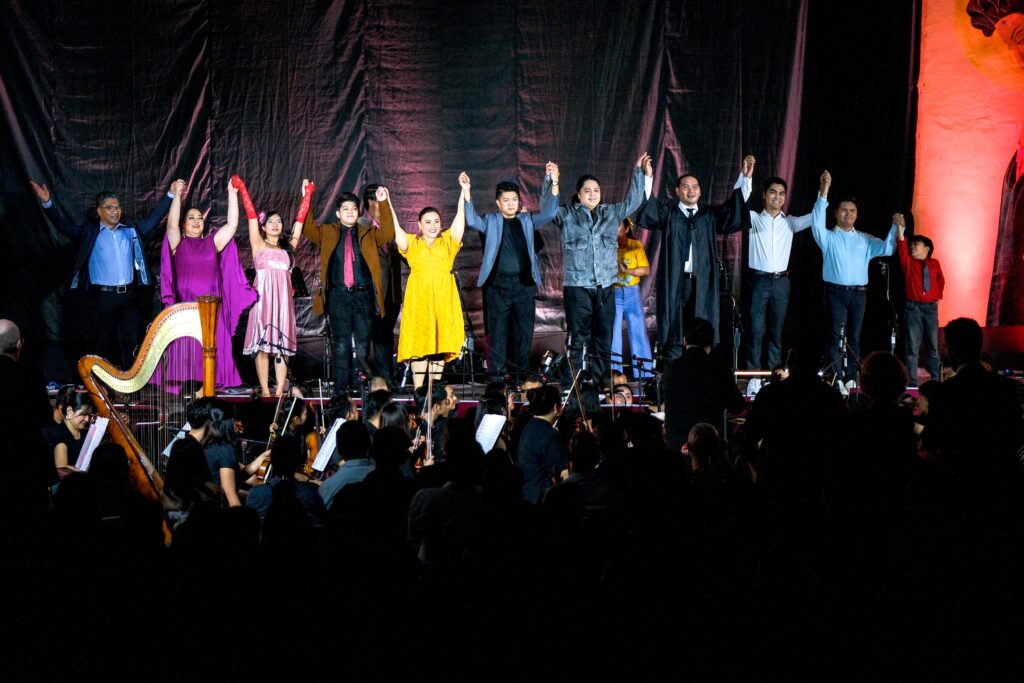

I was stumped at how the kids understood better when Puccini appeared so at home in Tondo: Gianni Schicchi, aided in Filipino, undistracted by another carnival ruse outside that big-top circus tent. Nothing seemed lost in translation.

The kids sat on the edge, giddy with eyes that had a roguish snap about them: at times peeled, sometimes closed to savor each sensation, sometimes misty in an ovation for an encore.

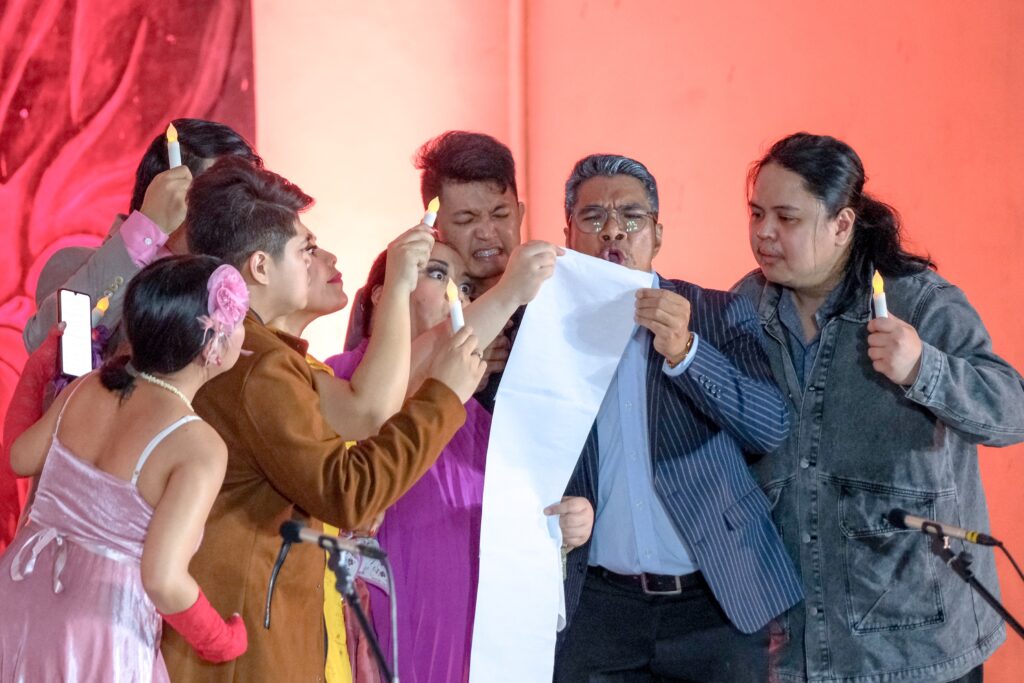

A family wrestled over inheritance, whose first impulse was to sing when they realized they got swindled by Gianni Schicchi (who also rejoiced in his rich baritone).

The young audience knew. And they laughed, some until they cried: “How foolish is that?” “What is wrong with you, sir?”

On a land where you endure on no apparent means, instincts are basic and humor simple. A rather slight folly wouldn’t be too hard to pick up, and the actors made use of every opening.

They would stumble, exaggerate a step and flail their arms. The children would laugh and you didn’t know why.

“What’s funny?”

Maybe the joke was on me.