(Part 2)

Joining the government was farthest from Rafael Alunan’s mind. He had always been a corporate guy in the private sector.

At the time, Alunan had just ventured into the manufacturing and distribution of shrimp feeds, a field that he was happy to work in. There was so much to look forward to because it was a sunrise industry. The sugar planters were banking on it to save them from total collapse or to get them out of the economic quagmire they had found themselves in.

“I was taken aback by Peter’s statement about me being there for an undersecretary’s position. I said, ‘Well, I don’t know. This is something new to me. I have to talk to my wife.’”

One relative who convinced him to join the Cory Aquino administration was his aunt, the daughter of his grandfather. “She was very close to Cory. Her name was Lourdes Fernandez. She was married to a man who belongs to the family who owns Compania Maritima.”

“She told me, ‘If the president calls, you have to answer.’ She believed in President Cory whom she sympathized with because she had by then already had to face a number of failed coup de etat. I joined her administration in June 1989.”

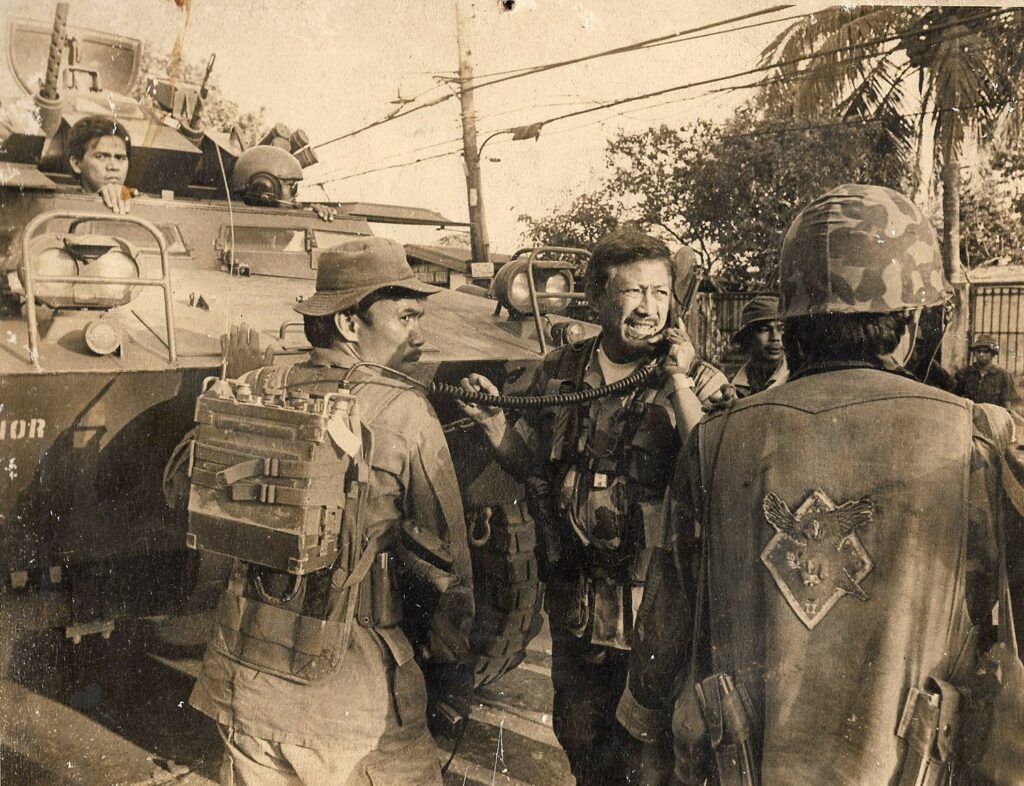

Baptism of fire

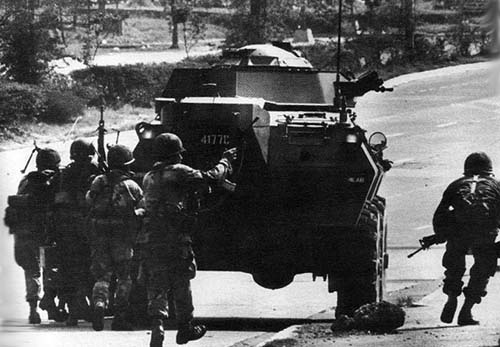

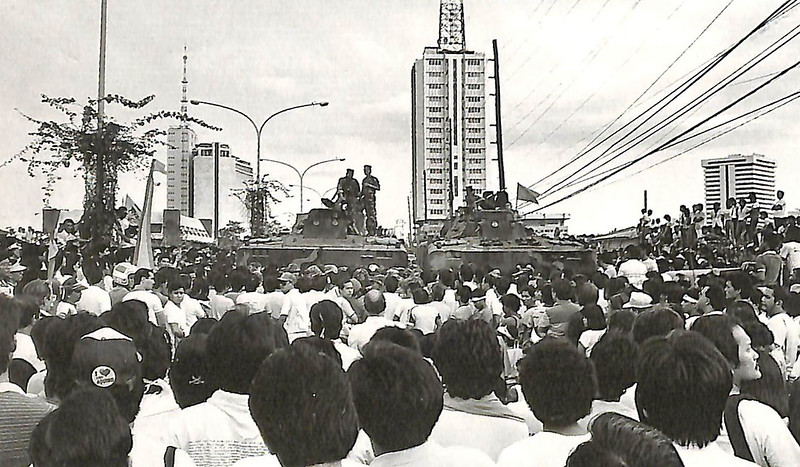

His baptism of fire came in December 1989, when a coup attempt had led to an impasse in Makati, with the rebels holed up in the Ayala Triangle.

Alunan recounted, “I was very much involved there. The first three, four days, I was in Crame. But right after, when I reported back to the DoT (Department of Tourism), we had another problem. The Scout Rangers had taken over Makati.”

Thousands, including tourists, were held hostage. He was given the marching orders to negotiate with the rebels and secure the tourists caught in the crossfire.

He aimed to get the tourists back to safety within 24 hours, at the longest. “I talked to the rebels, particularly their assigned negotiators and leaders.“

It was not easy. “When I was told that I had to come up with a plan, my first instinct was to probe. So I called Undersecretary Leo de Guzman of DoTC (what was then the Department of Transportation and Communications). I said, ‘Hey Leo, can you do a probe for me? Can you send a Love Bus inside Makati and see if we can fill it up with people who may want to escape?’ ‘Okay. Let’s do it,’ he said. So he sent a bus down Buendia instead of going through Ayala and EDSA. Because there were snipers at the Intercontinental Hotel who were shooting at anybody trying to come in.

“In Buendia, we could sneak up and sneak in from behind. There were government troops in the railroad tracks. The bus was not allowed to enter. So he called back and said, ‘Raf, no dice.’ So I called in the entire tourism industry. The travel agents, the hoteliers, the tour guides and everyone who had a direct hand in tourism services. I said, ‘Come on, let’s do a group think. Okay. I need to know from you what you think we can do to get the trapped tourists out of Makati. By midnight, no one had come up with any good idea.

“So believe me when I say that I went out there in the corridor dead of night and I went down on my knees and I prayed. I sank to my knees and I prayed and I said, ‘I don’t know what to do. We don’t know what to do. Help us.’ Basically that was my prayer.”

Lightbulb moment

“By one o’clock in the morning, I had a ‘ting’ moment, as though a bulb had lighted up on my mind. I said, ‘Can you get hold of our friends in the radio stations? I want to record something now — a message. And then I want them to run it every half hour. I was sure the tourists were listening and they wanted to find out what the hell was going on. So I wanted to give them some good news first. Like, say, when all this is over, you can go to these places at a discount. The Philippine Airlines will fly here and there and these hotels will be glad to serve you.’”

The hoteliers and PAL people had kept him company and waited for his instructions. “They were there with me. But the clincher was at the end of the message. My message was, ‘I now would like to direct my message to the Scout Rangers. Please call me at this number.’

“During the wee hours, I received maybe about four or five calls. They didn’t introduce themselves but they said, ‘Sir, we’d like to know what you’re up to. What’s on your mind? What do you want?’ So I told them the same thing. I wanted to talk to whoever was in charge of the Scout Rangers. I just wanted to discuss the release of the hostages who were trapped in the crossfire. ‘Yes, sir,’ came the reply. ‘Thank you.’ But after that, nothing happened. Around maybe four o’clock in the morning I called my good friend, a German, Max Motschmann, a diving instructor.’

“I called him because he was a kumpare (close male friend) of Gringo (Honasan). And I had a hunch Gringo was involved. And since we were a small community in skydiving, we knew each other. I said, ‘Hey, Max, I need your help. Can you call your kumpadre? Tell him I want to talk to the Scout Rangers. ‘Why him?’ I said, ‘you know very well why him. Don’t ask me.’ ‘I’ll see what I can do.’ Anyway, at nine o’clock in the next morning, my secretary came in and he said, ‘There’s somebody from a radio station who wants to talk to you. His name is Lambert Pabillon. Lambert Pabillon? What a strange name. Lambert Pabillon was from DZAM. I picked it up. Anyway, fast forward, I learned later on that he was a kumpare of Gringo. And the Rangers were using the station for their broadcast. The one who came on the line was Abe Purugganan.

“‘Yes, sir. I’m Abe Purugganan. I’m a major Scout Ranger. What can I do for you, sir?’ I said, ‘Before I answer that question, can you answer mine? ‘Yes, sir.’ I asked him, ‘Is it the habit of Scout Rangers to hide behind the skirts of tourists? ‘No, sir. We don’t do that.’ ‘Oh, that’s good. That’s what I wanted to hear from you. And I believe you. In this case, I think we can work together.’ ‘How, sir?’ ‘We’ll work together to save lives.’ ‘Help me get the trapped tourists out of the way because they’re getting caught in our crossfire.’ ‘And frankly speaking, I said, I don’t know why we’re fighting. Alright? But let’s just get them out of the way. Are you okay with that?’ ‘He said, ‘Yes, sir.’ ‘Good, wait for me there. Let’s negotiate.’ ‘And then he said, ‘Sir, before you do, please work out the ceasefire. It’s hard to negotiate while the shooting’s going on.’ ‘I said, sure.’ ‘By 4 o’clock, it was all set. But I was running late because I had expected to negotiate as early as 1 o’clock and finish before 6.

“By then, Cory had instructed Eddie Ramos, Eddie Ermita and Oca Florendo to communicate with me. General Florendo was in charge of civil-military operations. Alex Aguirre was the ground commander in charge of Makati.”

Caught in the crossfire

“Before negotiating with the rebels, I was told to talk to Aguirre, who was holding office at the Makati Fire Department, which served as the forward operating base, to get the final instructions from him. Only after that could I enter and talk to the rebels. My instruction was anything that was civilian in nature that pertained to the DoT, that was my decision. But if anything came up which was military in nature, we would have to decide on that. I told them that if I didn’t come back by 6 o’clock, they were to resume firing. Because it shouldn’t take too long to really come to terms since we already had agreed in principle to save lives.”

It was around one o’clock when he began talking with Aguirre. By two o’clock when I was ready to walk toward the hotels where the tourists were trapped, Abe Purugganan called through the radio station to say that I couldn’t come in yet because Egay Aglipay, who was on the side of the government, was still shooting at them. Obviously, he didn’t get the instructions for a ceasefire. He was the only one who didn’t know. He and his men were positioned at Zuellig, a two-story building near Urdaneta. I called up General Aguirre and told him about the situation. After a while, he called back to say that the shooting had stopped.

Alunan had two hours left. He then called up Leo de Guzman of DoTC and asked for the deployment of 50 Love Buses for the evacuation of the estimated 2,000 trapped tourists. As Manila was at a standstill, the buses became readily available. These were positioned in strategic places near the hotels.

“I then met with Lt. Col. Raffy Galvez, who headed the Rangers. He was followed by Major Abe Purugganan who, in turn, was followed by Captain Danny Lim (who would later become a general of the Scout Rangers). A Mistah and a newly minted Second Lieutenant Charlie Galvez also joined them. Years later, he would become chief of staff and then, Secretary of National Defense.”

It was a fast negotiation. Alunan related, “If I had a list of 10 demands or 10 issues, we quickly came to terms with nine. The 10th was the military one which I could not decide on. By that time, six o’clock had come. And we resumed fighting.

“I brought in the team who was with me — Max Motschmann, Major Lupisi who was detailed to me in the DoT, and Major Polo Diaz; also, two radio guys and one from a television network.

“We were caught in the crossfire. But we were inside Intercon. And for awhile, the generals on the government side were worried that we would be held hostage. I said, ‘Relax. I don’t think they’ll hold us hostage.’ But I wasn’t sure. And then two sergeants came in. And they reported to their leaders that some of our boys got hit by sniper fire. Special Action Force pala. They didn’t find out that I was from the Special Action Force, too. So I took advantage of the opportunity. And I said, ‘Give them to me. I will bring them to whatever hospital you want me to bring them to. And they’ll be under my protection. I can guarantee you that.’ And they said, ‘Thank you. We’ll talk about it. And we’ll consult General Brawner.’ Five minutes later, they said, ‘Sir, we’ll take care of our wounded. But we’ll escort you to where you came from so you can go back to your headquarters and figure out what to do with the last demand.’ The last demand was for government forces to pull back by one kilometer on all sides.”

No light, no water, no food

“So I reported to Secretary Ramos, General de Villa and General Biazon. Also present were Aguirre, Ermita and Oca Florendo. I told them about the last demand. Everything else was okay. And I said, ‘I think they’re ready to give up. There’s no light. There’s no water in Intercon. There’s no food. I found out that the rations were almost gone. And their ammo pouches were empty.

“The Air Force that they were expecting from Cebu was not coming. So I thought then that they were ready to negotiate. So I said, ‘If it’s alright, I’ll go home and sleep. Because I haven’t slept for four days. I was coming from Crame. And the generals said, ‘Yes, please go. They then called Arthur Boy Enrile. He was the superintendent of PMA (Philippine Military Academy). And he was highly regarded by the Scout Rangers. He negotiated with them.”

While Alunan was asleep in his home, at 3 a.m., Arthur called to tell him it was finished and that “I could get going by 7 a.m. to collect the tourists. But my mother-in-law, who evacuated from Makati and slept in our house, picked up the phone. And when she heard that the caller was a certain Enrile, she thought it was Johnny Ponce Enrile who, she knew, was on the other side. She decided not to give the phone to me.”

Later, she related to me that she was wondering, ‘Why would Johnny Ponce Enrile call my son-in-law at this time of the night?’ So you know what she said? ‘Can you please call in the morning? My son-in-law is very tired and sleepy.’”

Boy Enrile ended up staring at his phone. So, he called up Narz Lim and asked her to call Alunan to share the good news. “From 7 up to 11 in the morning, we had our trouble-free operation just collecting the tourists. We brought them to the duty free shops. We alerted all of the embassies to have their people man their tables there, and process their nationals. And then those who wanted to leave would be brought straight to the NAIA. Those who wanted to stay behind, could go back to their hotels. Or go to other hotels. Kasi (Because) by two o’clock, the shooting had stopped.”

Worst yet to come

By then, too, both sides were just negotiating the terms of their surrender. It was the end of 1989. Alunan had some time to relax although he kept working at the DoT.

It had been months since he joined the department, which he never dreamt of all his life. But there he was at the center of it all. Performing a crucial role in the nation’s history was far from his mind. He had hoped to return to Negros and help the poor sacadas and his townsmen, including the once mighty hacenderos who had lost their fortunes.

But it was also an opportune time to look back a little, even if he knew there was so much work to do. There was healing to be done, and he had no way of knowing that the country that he loved would experience the two worst disasters in its history as the 20th century was reaching its end — the killer earthquake of 1990 and the eruption of Mount Pinatubo in 1991, which wrought havoc on the whole Central Plains, snuffing thousands of lives, rendering thousands of families hopeless and drowning highways, villages and churches, its catastrophic effects on climate reaching the far ends of the world.

To be continued on 28 February