A new study about the potential of seaweed as a resilient food source was published in the scientific journal Earth’s Future by a team of researchers from the Alliance to Feed the Earth in Disasters, Louisiana State University, University of the Philippines Diliman Marine Science Institute and the University of Canterbury.

Researchers discovered that seaweed can be a crucial pillar for food security in abrupt sunlight reduction scenarios such as a nuclear winter. Seaweed is found to be resilient in adverse conditions, so its growth and potential to enhance food security increases after severe nuclear conflicts.

Using an empirical model based on the seaweed Gracilaria tikvahiae in combination with nuclear winter climate data, the researchers simulated global seaweed growth. The results demonstrated that seaweed has the capacity to be cultivated in tropical oceans even after a major nuclear war between Russia and the US.

Such a war would deliver 150 Tg of black carbon to the atmosphere and could block out the sunlight for years but enough to drive photosynthesis. This scenario leads to increased vertical mixing and decreased phytoplankton production, providing more nutrients to the seaweed.

Previous studies showed that agriculture and fisheries production would plummet, so alternative food sources like seaweed will be critical in ensuring good security in sunlight reduction scenarios. Ocean modeler Prof. Cheryl Harrison from the Louisiana State University said, “It’s only a matter of time before the latter [nuclear war and large volcanic eruption] happens, so we need to be ready. Because the ocean does not cool as rapidly as land, marine aquaculture is a very good option.”

Seaweed can be quickly scaled up to meet a substantial portion of global food application demand, reaching about 70 percent within just 7 to 13 months. Most of this can be used for animal feed and biofuel, as human consumption is limited to 10-15 percent due to the high iodine content in seaweed, which could cause adverse health effects.

In addition to the current benefits of seaweed farming, researchers have suggested investing in seaweed farming as a proactive measure for global food security, both now and after a catastrophe. This could potentially avert a significant number of deaths from starvation, according to resilient food expert Prof. Dr. David Denkenberger from the University of Canterbury.

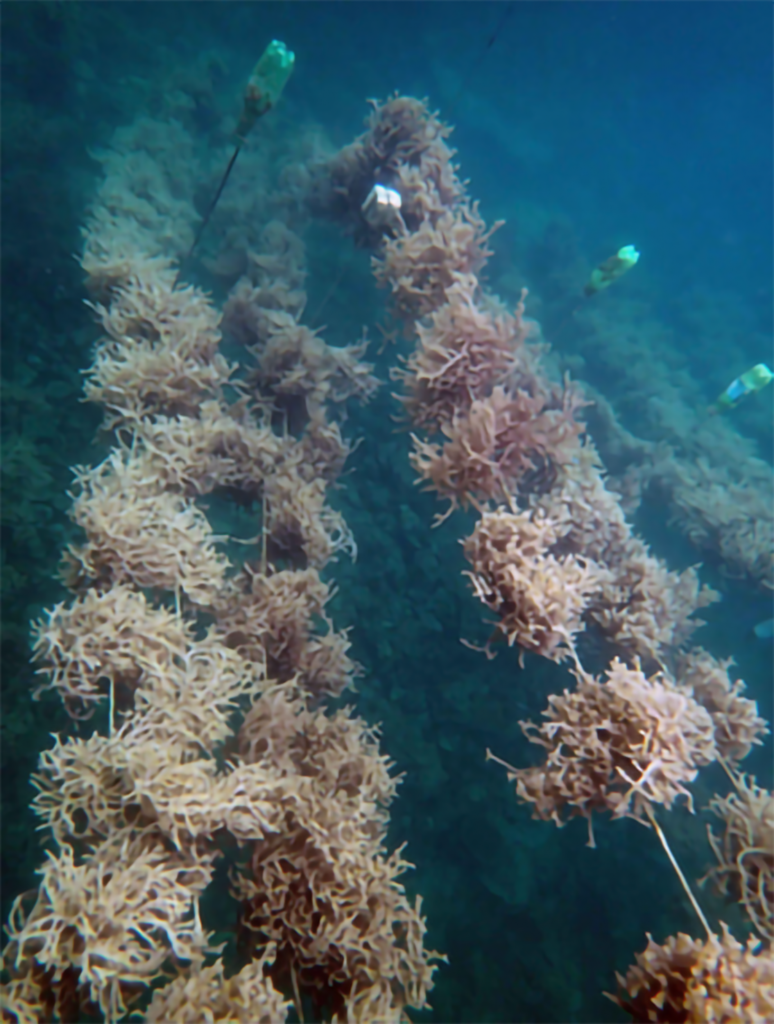

So far, low-tech seaweed farming is the commonly implemented method in the Philippines.

The preprint of this study was selected as one of the most exciting and interesting entries out of 17,000 submissions to the European Geosciences Union conference in Vienna (2023). According to lead author Dr. Florian Ulrich Jehn from ALLFED, the study opens avenues for further research on seaweed as a food solution after a nuclear war.

The UP Marine Science Institute is one of seven academic institutes of the College of Science, University of the Philippines Diliman. It aims to advance, disseminate and apply knowledge through research and development, and public service and extension in the marine sciences and related disciplines, playing a big role in shaping the discourse on Philippine waters.